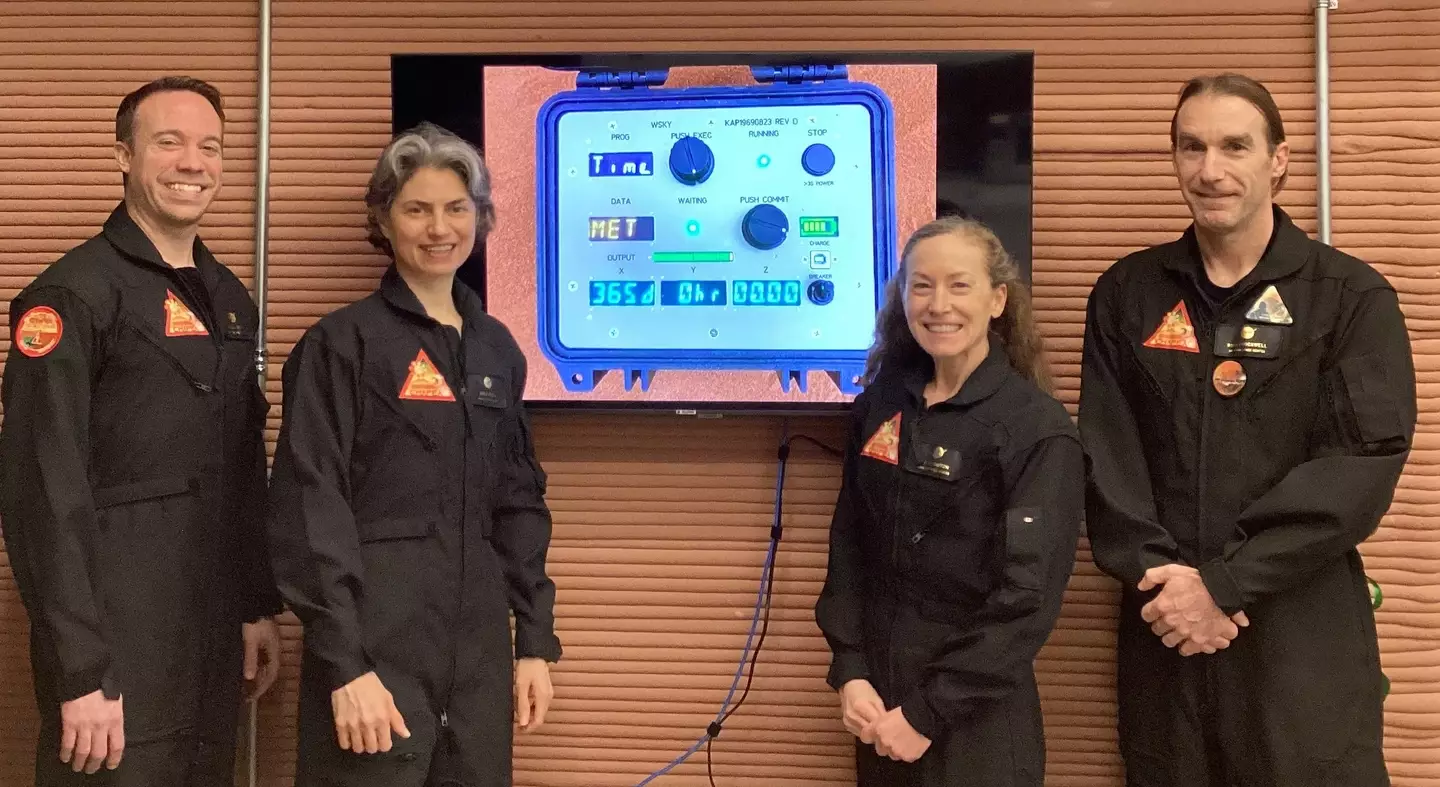

Imagine willingly locking yourself away for an entire year, completely cut off from the world as you know it. That’s exactly what a group of daring NASA volunteers did as they embarked on a year-long Mars habitat mission. The isolation many of us felt during the Covid-19 pandemic was tough, but at least we had the comfort of family. Asked to do it again, most of us would firmly refuse. Yet, four courageous astronauts – Kelly Haston, Anca Selariu, Ross Brockwell, and Nathan Jones – took on this challenge voluntarily, aiming to simulate life on Mars.

At 5pm (EDT), after 378 days, they stepped out of their ‘3D printed habitat’ located at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston. This habitat, a compact 1700-square-foot structure, included about nine rooms featuring communal areas, a shared bathroom, and private bedrooms. This mission, known as ‘Crew Health and Performance Exploration Analog’, was a pioneering endeavor by NASA to understand the dynamics of long-duration space travel.

NASA elaborated on the mission’s purpose in a statement: “The first Crew Health and Performance Exploration Analog (CHAPEA) mission began in the 3D printed habitat on June 25, 2023, with crew members Kelly Haston, Anca Selariu, Ross Brockwell, and Nathan Jones.”

During their year in isolation, the crew carried out ‘Marswalks’, grew vegetables to supplement their diet, maintained their habitat, and faced challenges like communication delays with Earth, resource limitations, and isolation – all factors that a real Mars crew would experience.

The CHAPEA team also included prominent NASA figures such as Steve Koerner, deputy director at NASA Johnson; Kjell Lindgren, NASA astronaut and deputy director of Flight Operations; Grace Douglas, principal investigator of CHAPEA; Judy Hayes, chief science officer of the Human Health and Performance Directorate; and Julie Kramer White, director of engineering.

This simulation was crucial for NASA to assess how well astronauts can cope in an alien environment, which greatly differs from Earth. Before sending humans to Mars, scientists need to understand the potential health impacts of space travel. Recent research by scientists at University College London (UCL) has raised concerns about the effects of microgravity and galactic radiation on the body, particularly on the kidneys. Dr. Keith Siew, one of the study’s authors, highlighted the risks in an interview with The Independent, noting significant health issues like kidney stones in astronauts on shorter missions.

Dr. Siew explained, “What we don’t know is why these issues occur, nor what is going to happen to astronauts on longer flights such as the proposed mission to Mars. If we don’t develop new ways to protect the kidneys, I’d say that while an astronaut could make it to Mars, they might need dialysis on the way back.” The findings underscore the importance of this simulated mission in preparing for the real challenges of interplanetary travel.