The Olympics are currently in full swing, and many viewers are tuning in to watch the fencing events.

As an amateur fencer myself, there are few things more exhilarating than watching two individuals in protective gear trying to score points against each other with their swords.

If you have ever observed a fencing match, once you grasp the concept of ‘right of way,’ you might notice something peculiar about the competitors.

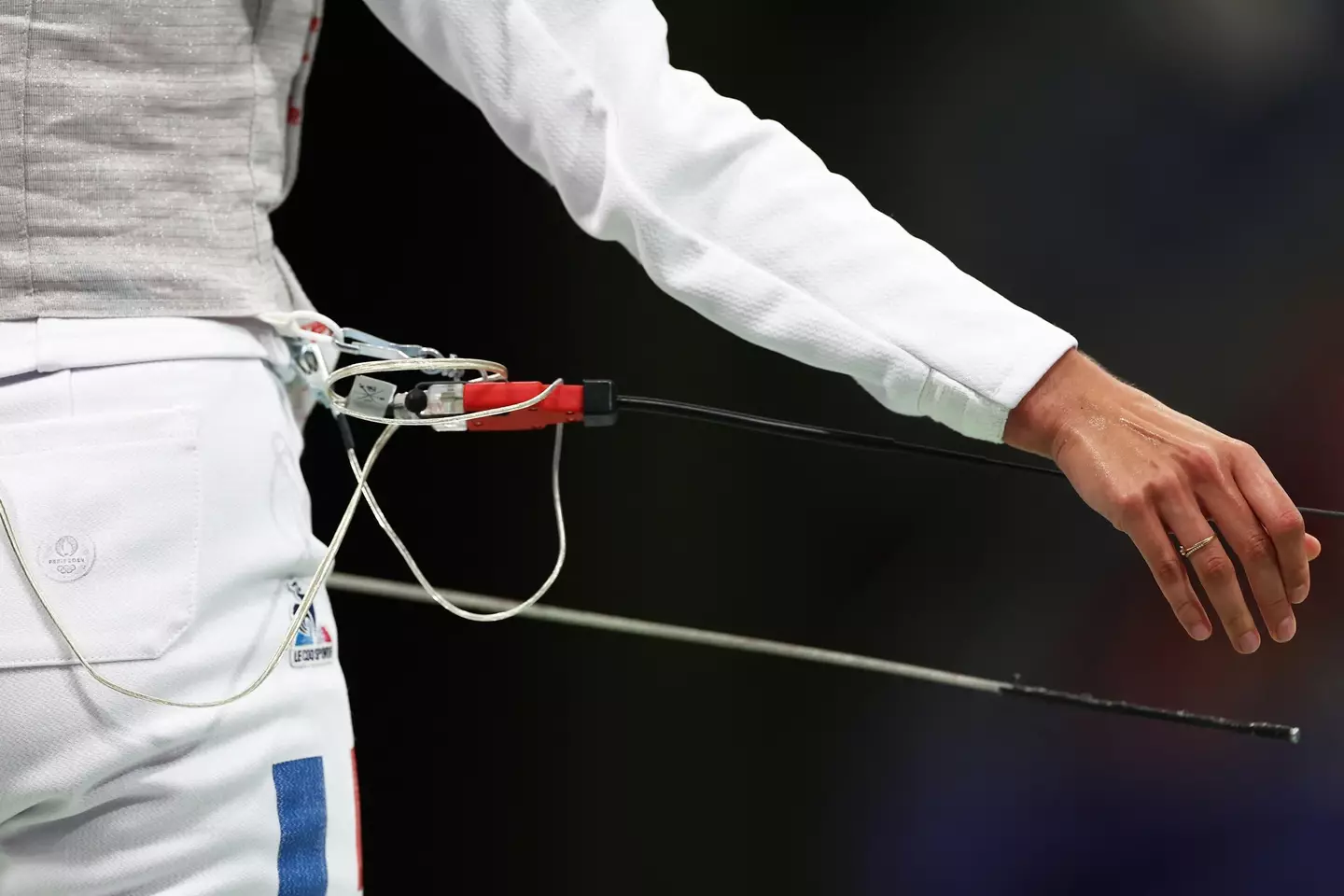

Typically, both fencers have a long cable attached to their backs, which is connected to a spool at the end of the piste.

In fencing terminology, the place where you compete is called a piste, similar to skiing.

There are many speculative theories as to why fencers attach themselves to one end of the piste, but the truth is that it’s a crucial aspect of conducting a fencing match.

Fencing is an incredibly fast-paced sport.

Hits can occur in a split second, and even the most attentive judge may find it challenging to determine who struck first and where the hit landed.

Both of these factors are essential in deciding who is winning the match.

The cables you see protruding from the fencers’ backs are not intended to prevent them from getting too close to each other.

Nor are they designed to stop you from stepping off the piste; the referee will call a halt if that happens.

Rest assured, these cables do not hinder your movement.

They are there to keep score.

The cable connects behind your back, with another wire running up inside your jacket and down your sleeve before plugging into your sword.

When a hit is registered, an electrical signal travels down the wire to a box, which activates a light and a buzzer to indicate a hit has occurred.

Different weapons in fencing have different rules.

In foil, you can only score by hitting the torso and neck, while in sabre, the target is the upper body.

Fencers also wear a jacket called a lamé, which is conductive.

This means that if you land a hit on target, the light turns green, and if it’s off target, it turns red.

Regarding ‘right of way,’ the rules vary, but essentially, in foil and sabre, it helps a judge decide who gets the point in the event of a double hit.

In the case of the third weapon, epée, which I believe is the best, the entire body is the target area with no right of way. Thus, if there’s a double hit, both fencers score a point.

As an epéeist, I might be slightly biased, but we prefer our straightforward rules: ‘hit them, don’t get hit.’

Lastly, ‘en garde’ means ‘get ready.’ The actual starting command is ‘allez,’ which is French for ‘go.’

So now you’re in the know – en garde, prêt, allez!