A human skull, estimated to be over a million years old, has the potential to change our current understanding of human evolution.

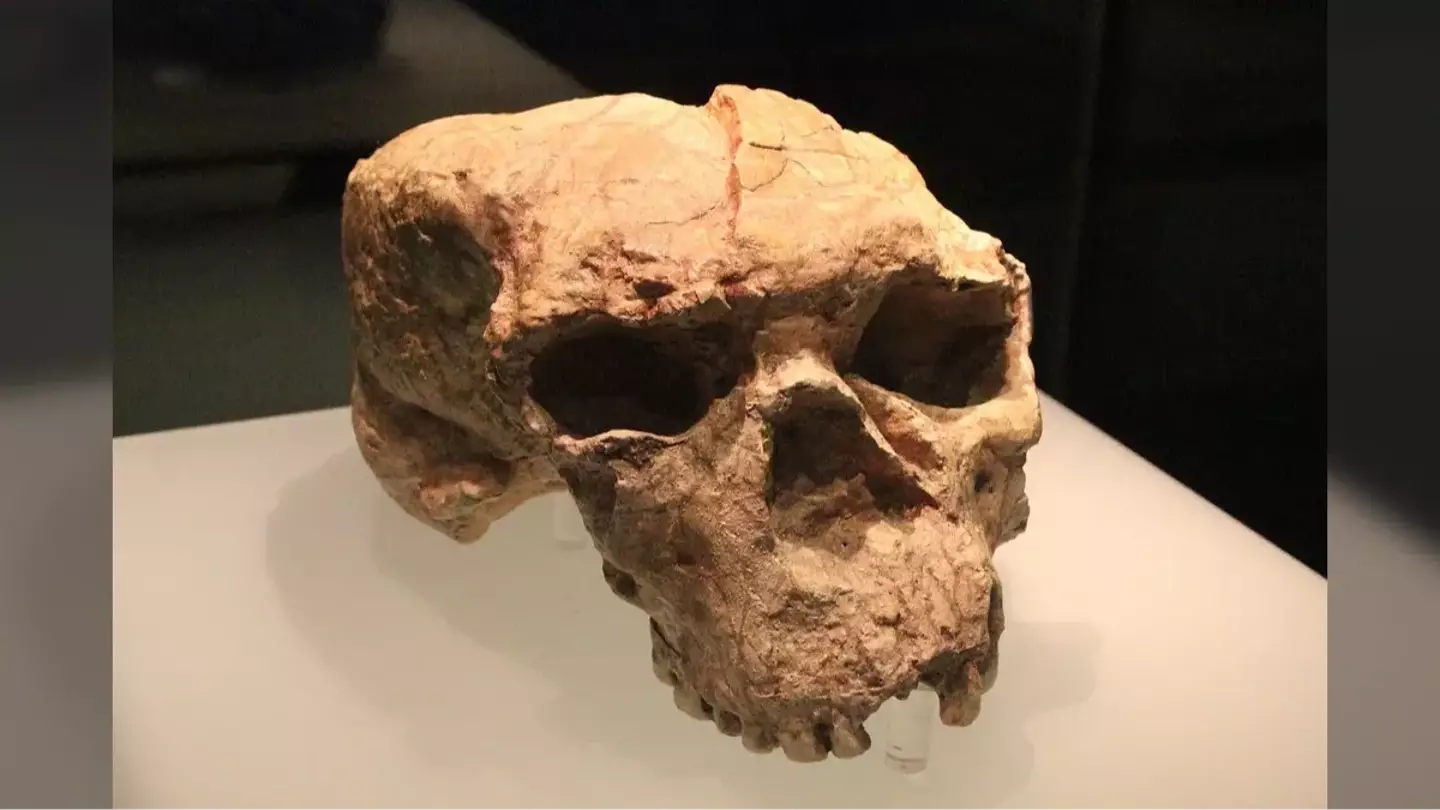

Prominent scientists have made a significant discovery after closely examining an ancient skull, named Yunxian 2, which was found in the Yunxian region of China’s Hubei province back in 1990.

The skull, which was in a severely damaged state, was initially thought to belong to the early human species Homo erectus due to its age and features such as a large brain case, prominent lower jaw, and other broad characteristics.

Recent analyses, however, suggest a new perspective: the shape and size of the brain case and teeth hint at a closer resemblance to Homo longi. If corroborated, this could imply that Homo sapiens may have first emerged outside of Africa, as stated by researchers in a study published in Science.

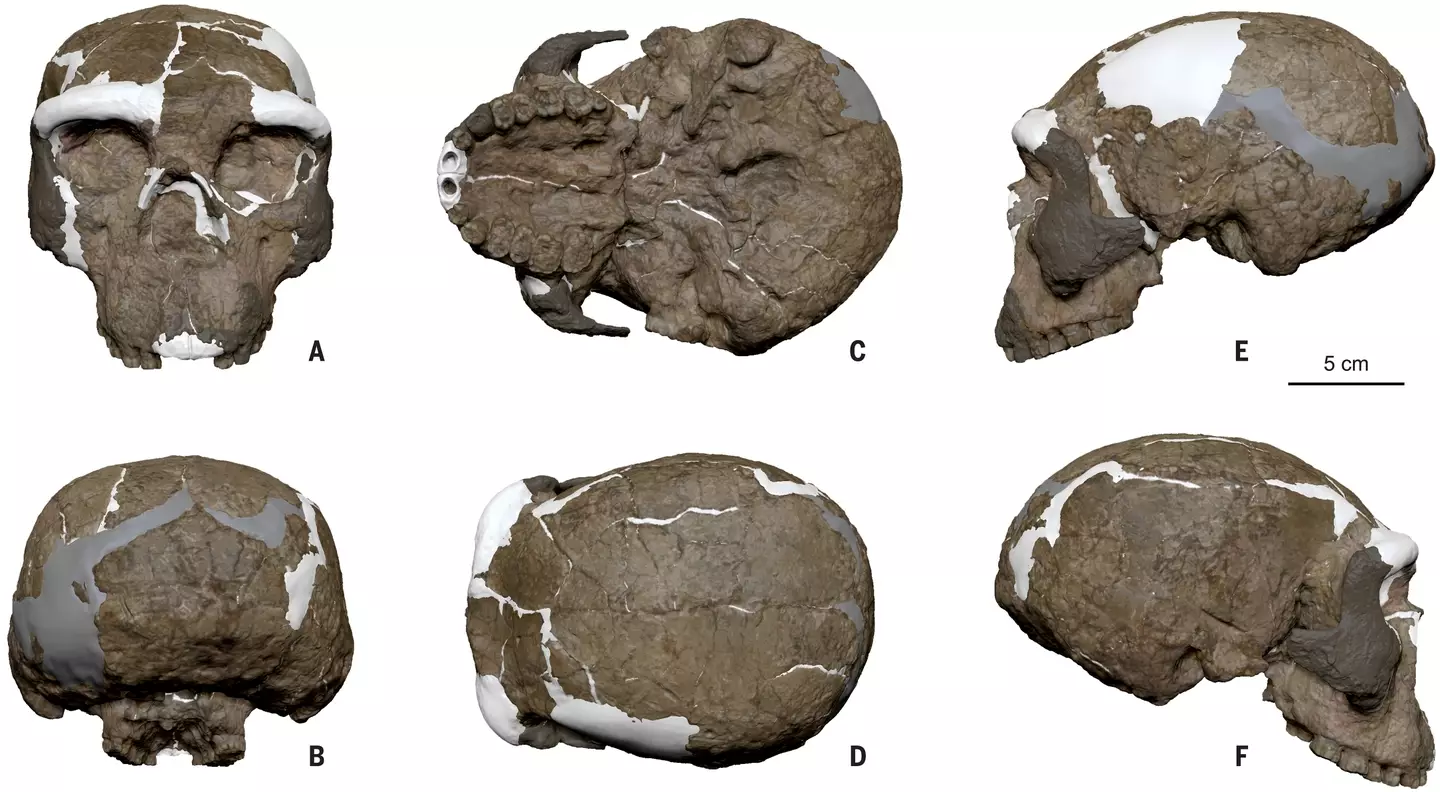

The research team employed modern reconstruction techniques on the bone, revealing it might be associated with a group more closely related to Denisovans, who coexisted with our early ancestors.

If confirmed, this finding would identify the fossil as the earliest evidence of a split between modern humans and our nearest relatives, the Neanderthals and Denisovans, by at least 400,000 years. This would offer a fresh perspective on early human physical characteristics.

Such a discovery would also significantly revise our historical understanding of human evolution over the past million years, suggesting that the initial emergence of Homo sapiens might have occurred in Western Asia rather than Africa.

Professor Chris Stringer, an anthropologist and research leader in human evolution at the Natural History Museum in London, remarked: “This changes a lot of thinking because it suggests that by 1 million years ago our ancestors had already split into distinct groups, pointing to a much earlier and more complex human evolutionary split than previously believed.

“It more or less doubles the time of origin of Homo sapiens.”

He further noted: “This fossil is the closest we’ve got to the ancestor of all those groups.”

The study utilized advanced CT imaging and digital techniques to create a virtual reconstruction of the skull.

“We feel that this study is a landmark step towards resolving the ‘muddle in the middle’ that has preoccupied palaeoanthropologists for decades,” the professor added.

Dr. Frido Welker, an associate professor in human evolution at the University of Copenhagen, who was not part of the research, also commented: “It’s exciting to have a digital reconstruction of this important cranium available,” as reported by The Guardian.

“If confirmed by additional fossils and genetic evidence, the divergence dating would be surprising indeed. Alternatively, molecular data from the specimen itself could provide insights confirming or disproving the authors’ morphological hypothesis.”