Astrobiologist Alyssa Carson has shared her aspiration of traveling to Mars, but she has also highlighted the numerous challenges involved in making this journey.

In the realm of science fiction, humanity is often depicted as having already reached Mars and beyond. However, in reality, the scientific and technological hurdles required to send a human to the red planet are complex and fraught with difficulties.

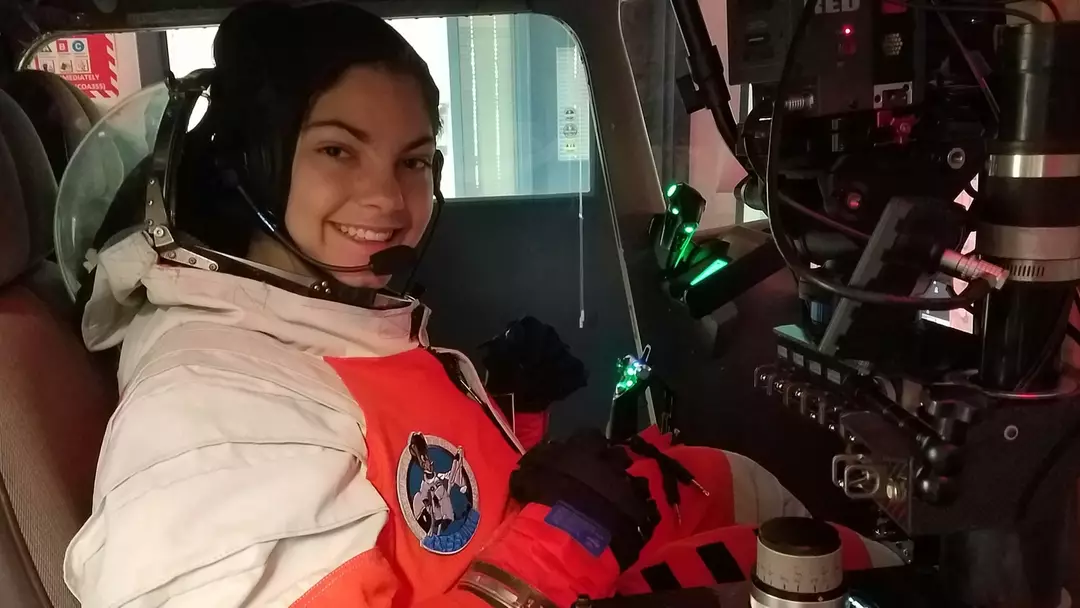

Alyssa Carson, a 24-year-old astrobiologist and science communicator, has been fascinated by space exploration and Mars since her childhood. She has pursued a career that could significantly enhance our understanding of Mars.

Carson, in a conversation with UNILAD, discussed her ambition to be the first person on Mars, a goal she frequently shares on social media. She explained that while Mars exploration remains a goal, her current focus is on equipping herself with the necessary skills before applying to become an astronaut.

She pointed out that reaching Mars is not as simple as portrayed in animations or films, and a multitude of issues must be resolved before humans can walk on the Martian surface.

Discussing the progress towards this objective, she stated: “NASA has formed a significant partnership with the European Space Agency (ESA), and they are collaborating more closely with the new Artemis program.”

“So I think that is very promising. We are hopefully having a new Artemis launch. I think their launch window opens next month. So we are very much on the verge of sending people back to the moon.”

Carson remarked that this is a positive development, bringing us closer to reaching Mars. She further noted that having a regular presence on the moon could pave the way for establishing a permanent base, which would aid in Mars exploration.

However, she acknowledged that one of the primary challenges of a Mars mission is the timeline.

Carson elaborated: “With the older engines that they were looking at, you know, they were saying it’s going to take, you know, six to nine months just to go from Earth to Mars, then you have to live on Mars for a while, then come back. And that’s definitely a lengthy mission.”

A recent NASA article featured Orbital Dynamics expert Brent Barbee confirming the duration of a Mars journey, explaining that the planet is about 50 percent further away from the Sun than Earth. He added: “NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter mission took about seven and a half months to reach Mars. And NASA’s MAVEN mission took about ten months to reach Mars.”

While reaching Mars is a significant hurdle, it is compounded by three additional challenges.

The extended mission duration necessitates a reliable food supply, a task that presents its own set of challenges—consider the amount of food consumed over nine months.

NASA scientists Grace Douglas, Sara Zwart, and Scott Smith have emphasized that even shorter missions encounter food-related issues concerning safety, taste, nutrition, and dependability.

Mars is depicted as a highly radioactive environment in media, and prolonged exposure to this radiation poses similar problems as those faced on Earth regarding radiation exposure.

Jonathan Pellish, a space radiation engineer at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, has noted: “There’s a lot of good science to be done on Mars, but a trip to interplanetary space carries more radiation risk than working in low-Earth orbit.”

The impact of microgravity on the human body over an extended period is another significant concern.

While the reduced gravity might seem beneficial, it leads to well-documented issues.

A 1992 study by NASA scientists JW Wolfe and JD Rummel highlighted critical concerns such as ‘negative calcium balance resulting in the loss of bone, atrophy of antigravity muscles, fluid shifts and decreased plasma volume and cardiovascular deconditioning that leads to orthostatic intolerance’.

Addressing these challenges, Carson acknowledged that progress is being made to reduce travel time, which would mitigate some issues.

She commented: “There’s a lot of issues that just come with the sheer length. So, I mean, I think a big goal that they’ve been looking at is getting newer engines, newer technology. I know a big goal was to develop newer engines, to reduce that time from six months to six weeks. So I think that that’s where we’re kind of hovering right now.”