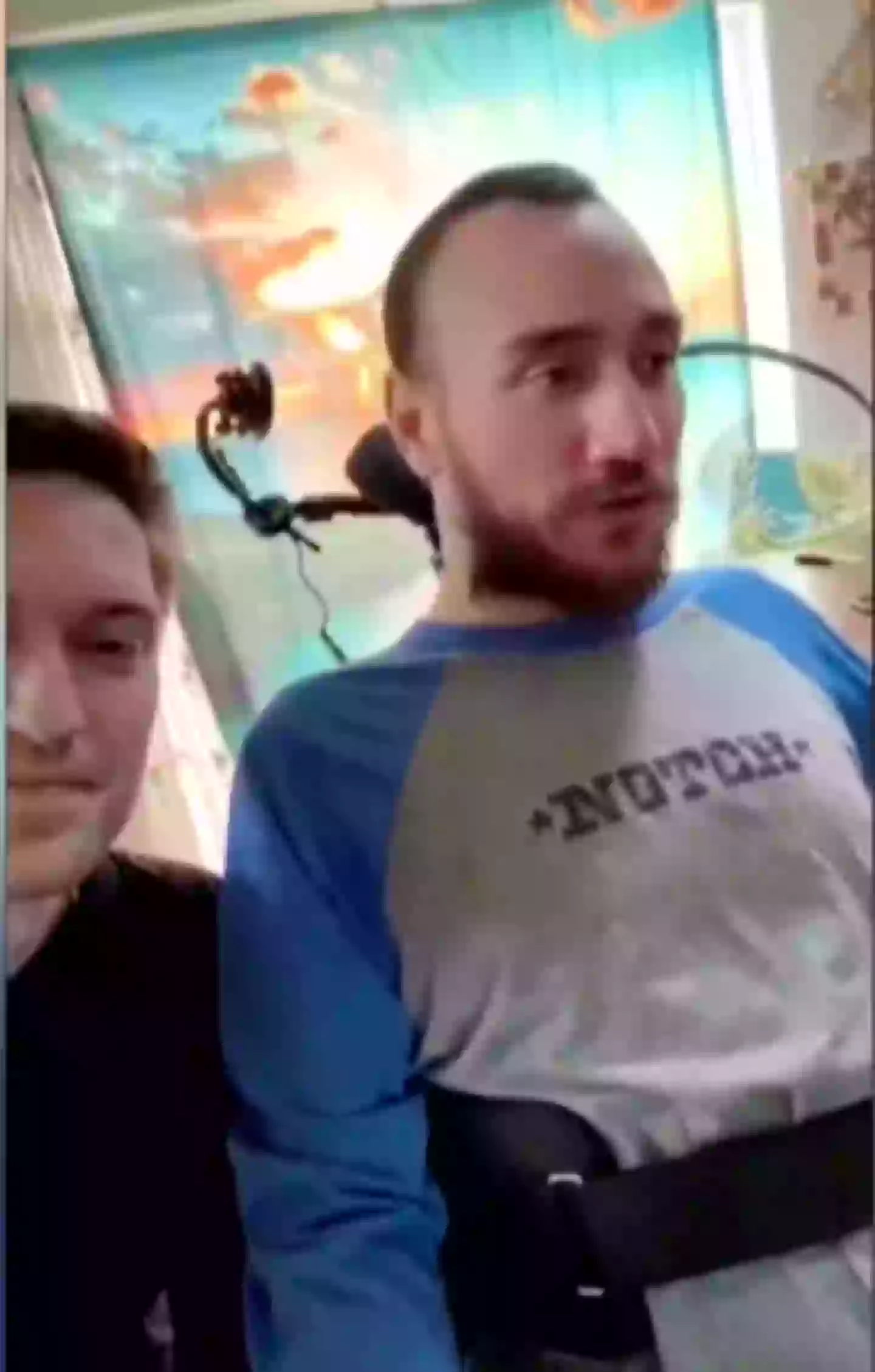

An Arizona man, Noland Arbaugh, has made history as the first individual to receive a ‘mind-reading chip’ from Neuralink, Elon Musk’s neurotechnology company. The procedure took place in January 2024, marking a significant milestone in neural interface technology.

Noland’s life took a drastic turn in 2016 when a diving accident left him paralyzed from the shoulders down. This incident threatened his ability to work, pursue education, or enjoy recreational activities. He shared with the BBC, “You just have no control, no privacy, and it’s hard.

“You have to learn that you have to rely on other people for everything,” he continued.

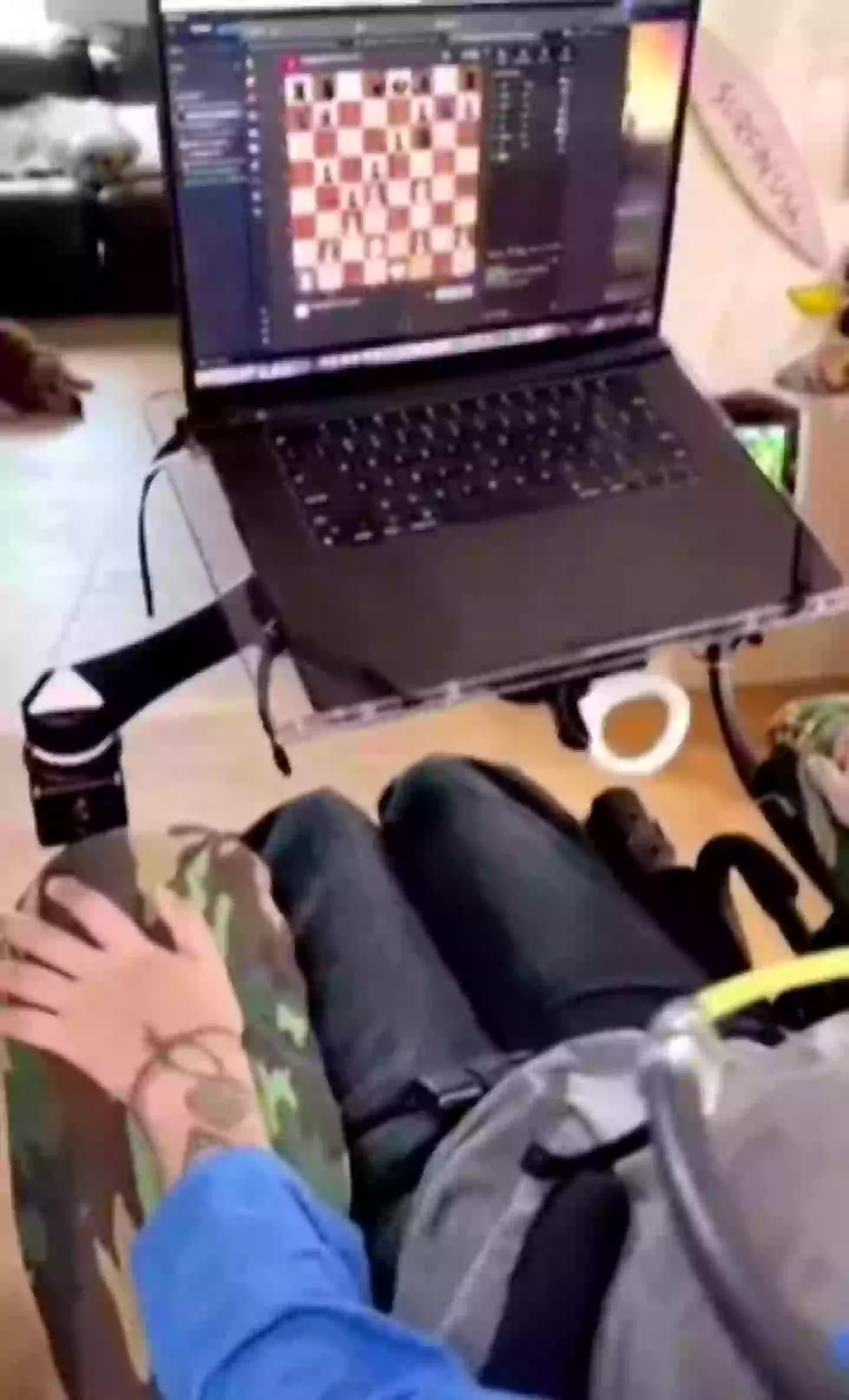

The Neuralink chip has offered Noland a newfound independence by enabling him to control a computer independently through his thoughts. This brain-computer interface (BCI) chip operates by detecting the small electrical impulses generated when we think, translating them into digital commands.

Post-surgery, Noland noticed immediate changes. He found himself able to move a cursor on the screen merely by thinking about finger movements. “Honestly I didn’t know what to expect – it sounds so sci-fi,” he admitted.

As he observed his neurons in action, the reality hit him that he could manage his computer through his mind alone.

Noland has since refined his skills with the device, achieving the ability to play video games and even outperform his friends, a feat he describes as improbable yet true.

While neural interface technology has been a research focus for years, Neuralink, under Musk’s leadership, has amplified its prominence in the tech world.

Before the procedure, Noland met with Elon Musk, noting Musk’s excitement about the project. However, Noland emphasizes that the technology extends beyond Musk’s influence, stating it is not simply an “Elon Musk device.”

Despite being a technological breakthrough, the Neuralink chip raises privacy concerns. Anil Seth, a Neuroscience Professor at the University of Sussex, cautions that exporting brain activity could expose personal thoughts, beliefs, and emotions. “Once you’ve got access to stuff inside your head, there really is no other barrier to personal privacy left,” he noted.

Noland did encounter some challenges, such as the device losing connection and control over his computer, which he described as “upsetting to say the least.” Fortunately, the issue was resolved, and the connection improved.

Looking ahead, Noland is hopeful about the potential advancements of the chips, such as controlling a wheelchair or even a humanoid robot. However, his participation in the study is limited to six years, leaving his future after that period uncertain.