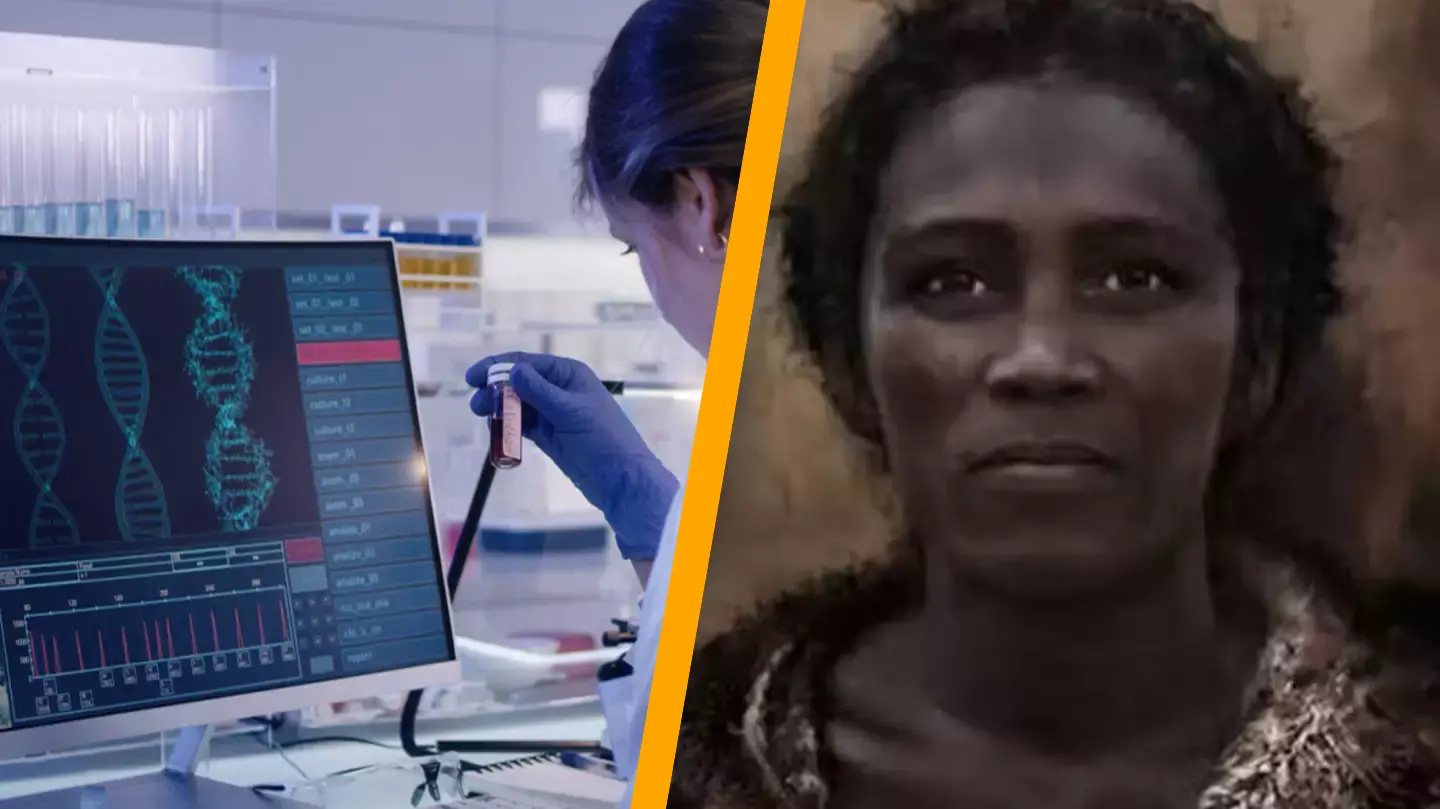

A groundbreaking investigation has uncovered ancient DNA that may potentially unlock the enigma of a vanished lost race.

This research has shed light on the impact our Neanderthal relatives had on life as it is today, and the results could necessitate a reevaluation of modern human history.

These ancient humans settled in Europe over 45,000 years ago, with findings indicating their population was quite small—possibly only around 200—according to researchers involved in the study.

Scientists examined remains from Germany’s Ranis area, revealing close familial ties, including a mother-daughter pair.

As reported by the BBC, the study indicates that humans and Neanderthals interbred, which provided protection against certain diseases, leading to the extinction of humans who did not interbreed with Neanderthals.

Professor Johannes Krause, from Germany’s Max Planck Institute of Evolutionary Biology and the study’s senior author, stated to the BBC: “We see modern humans as a big story of success, coming out of Africa 60,000 years ago and expanding into all ecosystems to become the most successful mammal on the planet.

“But early on we were not, we went extinct multiple times.”

These humans disappeared from Europe approximately 40,000 years ago, coinciding with the Campanian Ignimbrite eruption, a catastrophic volcanic event that likely resulted in the demise of humans and animals.

Professor Krause further commented: “This is the oldest genome of modern humans, and it represents a lineage that no longer exists.”

“We believe all human groups in Europe at the time – including Neanderthals – went extinct, and none contributed to the genetic makeup of people alive today.

“This genetic ‘package’ possibly explains why our species became so successful, ultimately growing to a global population of eight billion.”

Following this devastating extinction event, researchers suggest that Europe was repopulated by descendants of humans who had migrated further afield before returning.

Professor Krause mentioned to the BBC: “Both humans and Neanderthals go extinct in Europe at this time. If we as a successful species died out in the region then it is not a big surprise that Neanderthals, who had an even smaller population went extinct.”

Professor Chris Stringer from the Natural History Museum in London provided an independent perspective on the findings.

He noted that the study reveals ‘Neanderthals were very low in numbers’ during their final existence on Earth, and were ‘less genetically diverse’ than their human contemporaries.