A marine organism has achieved what humans have been attempting for ages – reversing the aging process.

Biohacker Bryan Johnson has been chronicling his efforts to halt aging, spending millions of dollars in the process.

In recent months, Johnson underwent a grueling procedure involving ‘300 million stem cells’ being injected into his joints to align them with his ‘total bone mineral density’.

However, scientists have recently found that comb jellies possess a far more affordable and painless method to counteract aging.

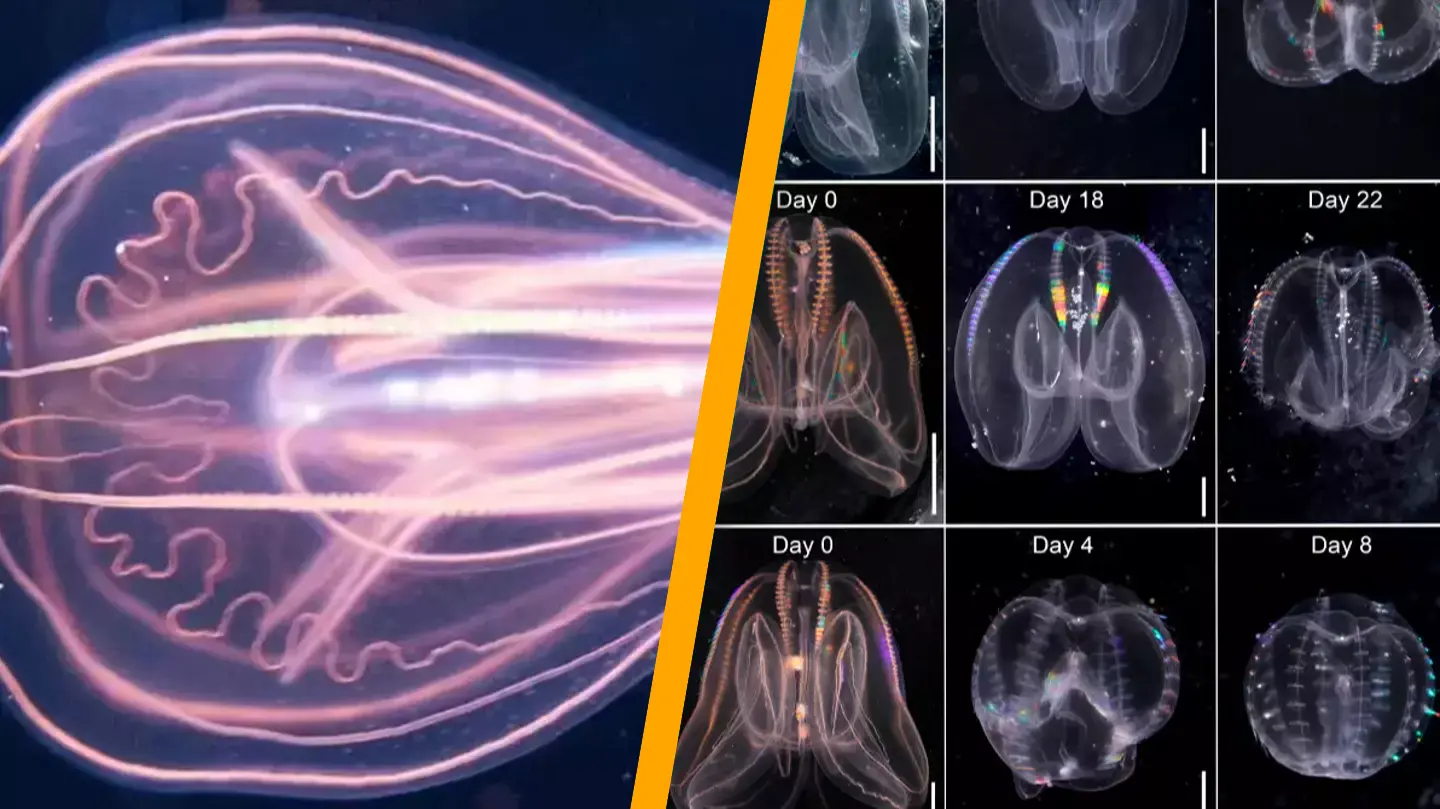

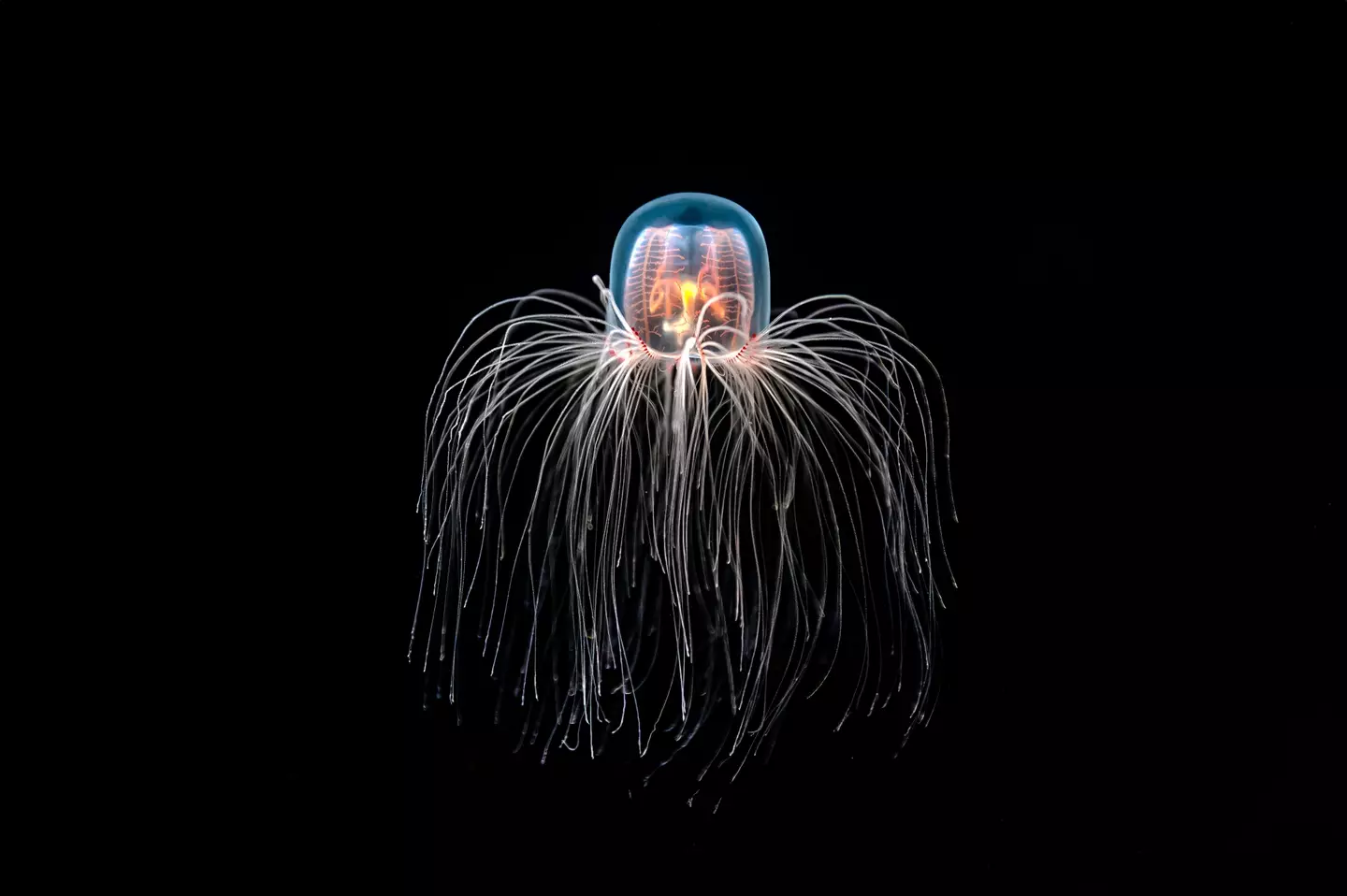

Comb jellies, scientifically known as Mnemiopsis leidyi, and also referred to as ctenophores, have been labeled ‘immortal’—much like the renowned Turritopsis dohrnii—following new findings that reveal these unique sea creatures can revert from an adult medusa to a polyp stage.

A recent publication in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences highlights how this discovery has reshaped previous understandings of animal life cycles.

Joan J. Soto-Angel, a postdoctoral fellow at the Department of Natural History at the University of Bergen, commented: “The work challenges our understanding of early animal development and body plans, opening new avenues for the study of life cycle plasticity and rejuvenation.

“The fact that we have found a new species that uses this peculiar ‘time-travel machine’ raises fascinating questions about how spread this capacity is across the animal tree of life.”

Like many groundbreaking findings, Soto-Angel discovered the rare life cycle of the marine animal by accident.

He began delving into the topic after observing that an adult ctenophore disappeared from a tank and seemed to be replaced by a larva.

This observation led Soto-Angel and Pawel Burkhardt, group leader at the Michael SARS Centre at the University of Bergen, to investigate the hypothesis that the larva in the tank was indeed the same being as the previously present adult.

Experimental investigations revealed that when subjected to the stress of starvation and physical harm, the creature exhibited an astonishing capacity to transition from its lobate form back to a cydippid larval stage.

“Witnessing how they slowly transition to a typical cydippid larva as if they were going back in time, was simply fascinating,” Soto-Angel recalled.

“Over several weeks, they not only reshaped their morphological features, but also had a completely different feeding behavior, typical of a cydippid larva.”

Burkhardt expressed that the discovery marks ‘a very exciting time for us’.