An underwater landmass once comparable in size to Spain has been identified beneath the ocean’s surface.

Though technically no longer an island due to its complete submersion, this seamount provides significant geological insights into Earth’s ancient landscapes.

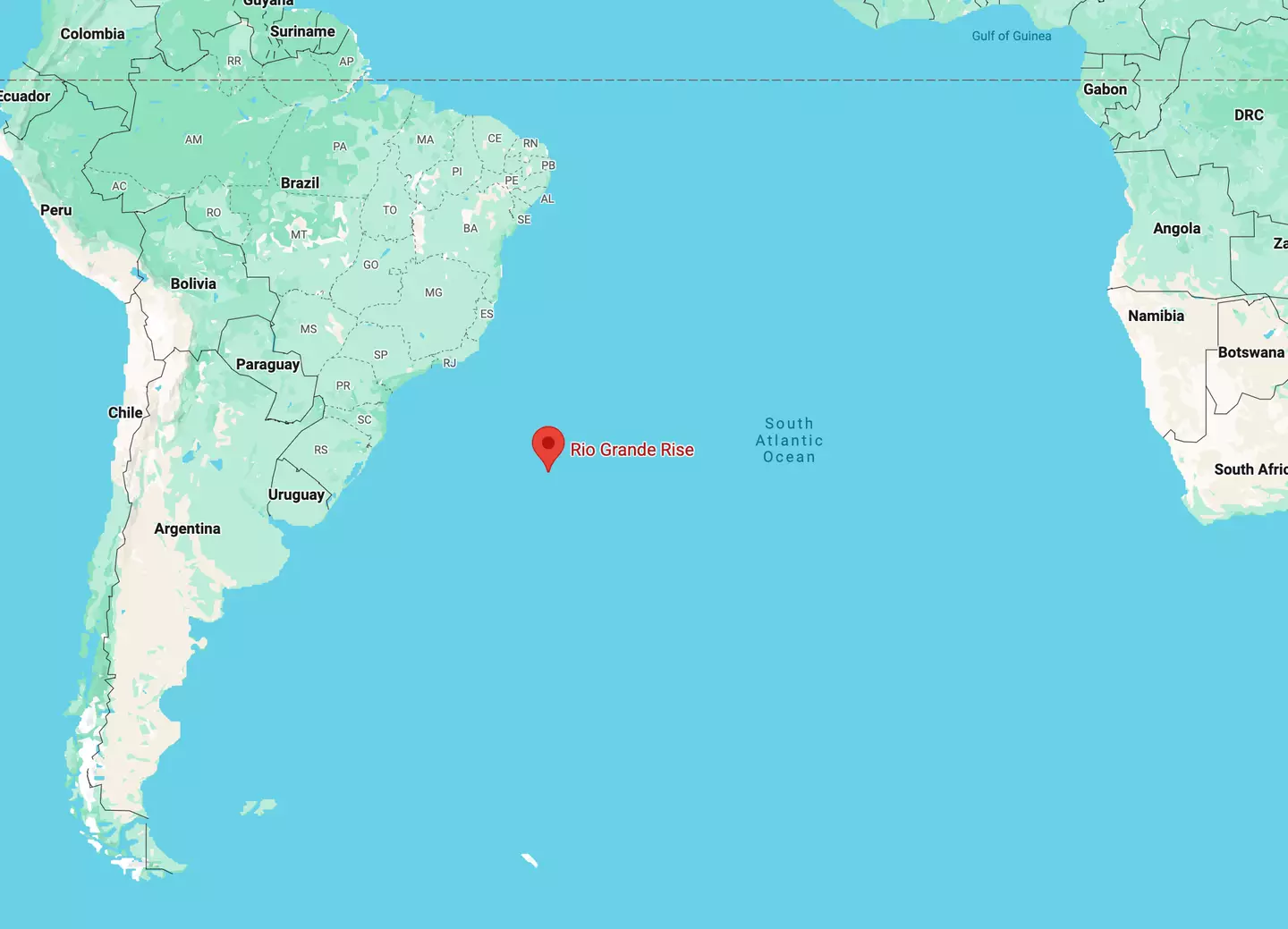

For those who may not be familiar, a seamount is an underwater mountain with steep sides that rise from the ocean floor. This particular formation is called the Rio Grande Rise and is located approximately 750 miles off the Brazilian coast.

The Rio Grande Rise differs from most other seamounts in that scientists believe it was once a thriving tropical island.

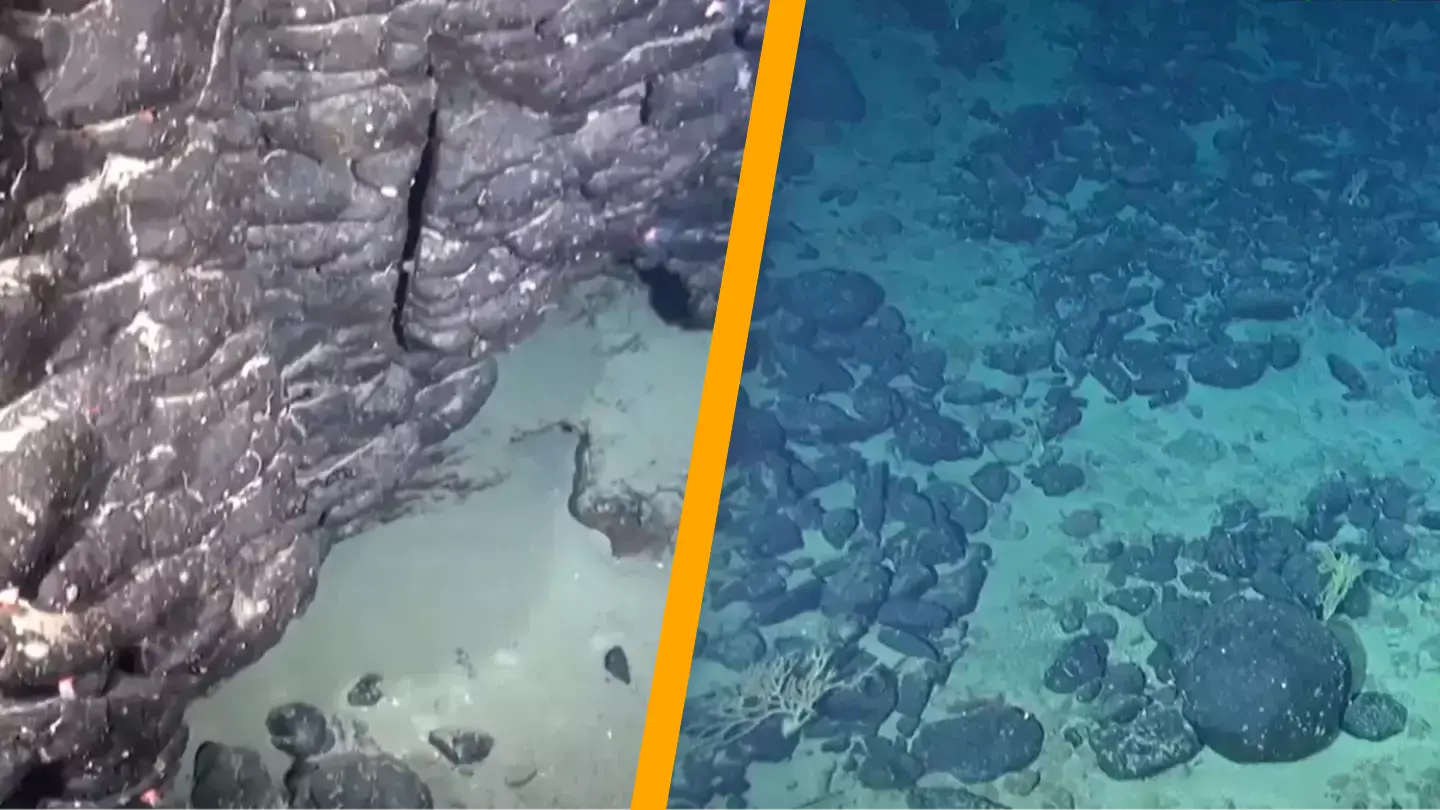

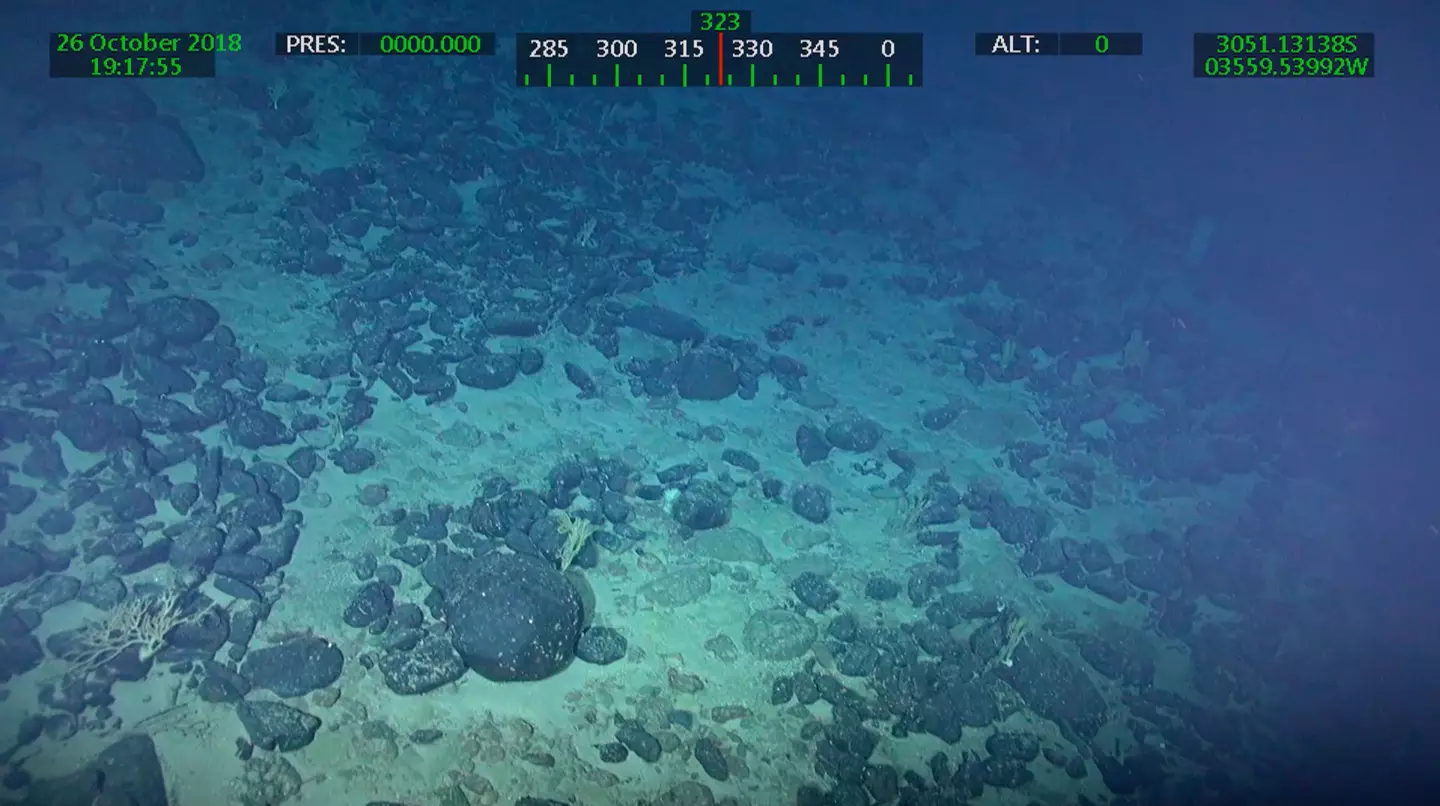

The seamount’s existence was noted over a decade ago, but in 2018, researchers discovered deposits of red clay about 650 meters below the surface. This is unusual because such minerals are not typically found in that region.

Marine geologist Bramley Murton told Eos: “You just don’t find red clay on the seabed.”

Further research indicated that the island’s history dates back about 80 million years to the Cretaceous Period, when dinosaurs roamed the planet.

The seamount was formed by volcanic activity and later sank beneath the ocean after drifting westward. Another eruption 40 million years later resulted in the mineral deposits found today.

These deposits include valuable rare earth minerals like cobalt, lithium, nickel, and tellurium.

These elements are critical for a wide range of industrial uses.

Notably, these minerals are essential for manufacturing rechargeable batteries used in devices like computers, electric vehicles, and smartphones.

While it isn’t a literal goldmine, it certainly represents a lucrative opportunity.

This discovery has raised questions about the control and ownership of the site’s natural resources.

Brazil has laid claim to the area, but the challenge lies in its location in international waters, beyond Brazil’s jurisdiction.

Brazil might argue that the region shares geological features with its landmass, categorizing it as part of Brazil’s ‘coastal shelf’ to assert rights over the resources.

Luigi Jovane, a professor at the University of São Paulo’s oceanographic institute, said: “Our research and analysis enabled us to determine that it was indeed an island, and what’s now under discussion is whether the area can be included in Brazil’s legally recognized continental shelf.”

There are also concerns about the environmental impact of extracting these minerals.

Jovane continued: “To know whether resources can be viably extracted from the sea floor, we need to analyze the sustainability and impacts of this extraction. The ecosystem services provided by the ocean there haven’t been studied in detail, for example.

“When you interfere with an area, you have to know how this will affect animals, fungi and corals, and understand the impact you’ll have on the cumulative processes involved.”