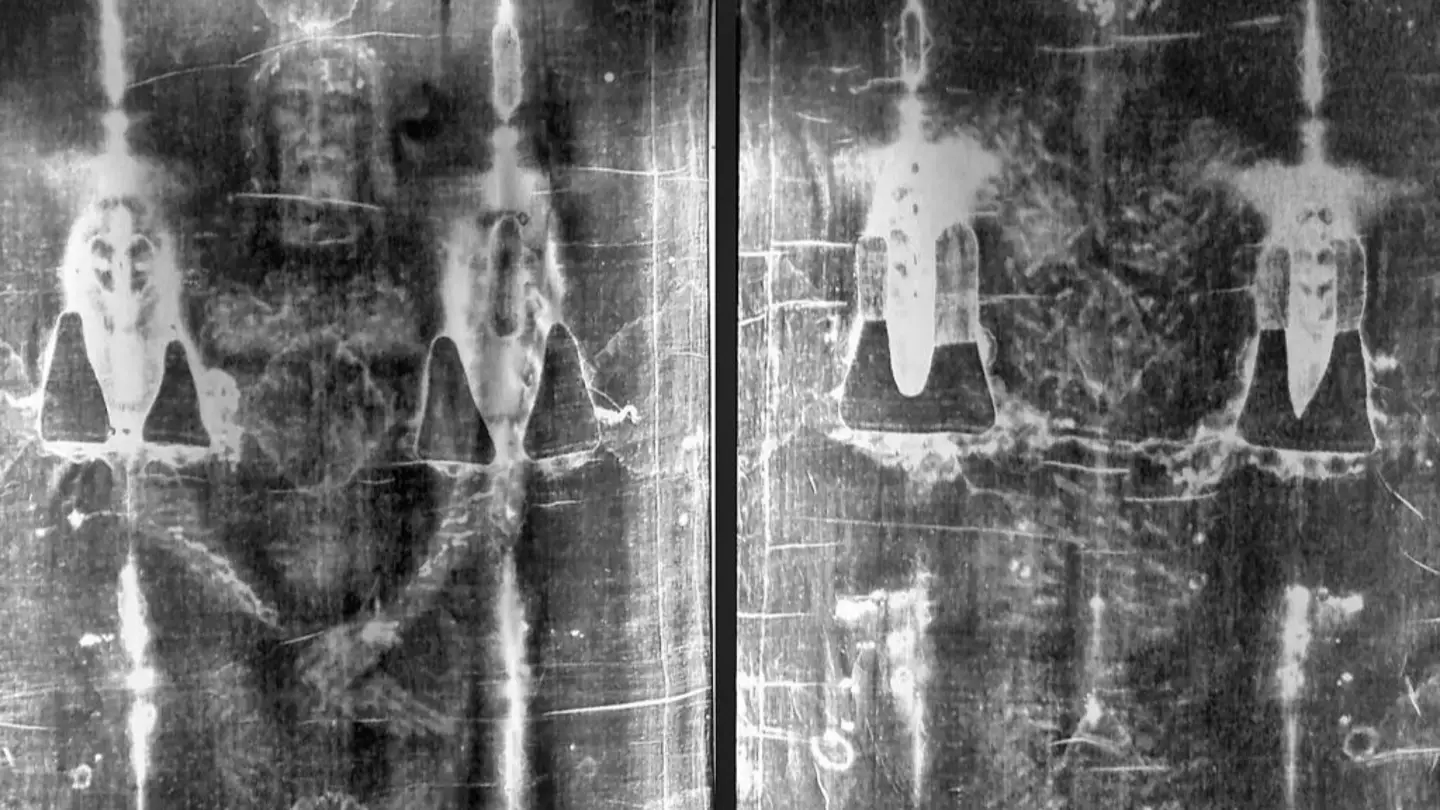

Recent studies on the biblical ‘Shroud of Turin’ suggest it might be more closely associated with Jesus than previously believed. The cloth’s history dates back several centuries, with recorded references starting around 1353. Traditionally seen as a religious artifact, the shroud depicts a crucified man with injuries that align with Biblical descriptions.

For Christians, the ‘Shroud of Turin’ could potentially be the burial cloth of Jesus, as the Bible mentions his body being wrapped in spices and a lengthy linen fabric. A 1998 investigation had claimed Jesus’ body was cleaned before burial, contradicting scriptural accounts. However, new scientific insights now challenge this assertion.

Dr. Kelly Kearse, an immunologist with training from Johns Hopkins University, has revisited the ‘washing hypothesis’ by analyzing how blood transfers onto cloth under post-mortem conditions, as reported by The Daily Mail. His research suggests that the blood stains on the shroud came from an unwashed body, which aligns with Jewish burial customs that disallowed washing the deceased if they died violently.

This belief stems from the idea that any blood lost in such events is part of the body and should be interred with it. Dr. Kearse also identified serum halos and distinct rings on the Shroud, indicating that the blood had clotted before reaching the fabric, supporting the notion that it came from fresh, unwashed wounds.

Previously, forensic pathologist Dr. Frederick Zugibe argued that if the shroud had been in contact with an unwashed, crucified body like Jesus, it would display large blood smudges. However, experts note that his study had limitations, as he used accident victims for his conclusions.

Dr. Kearse disputes the pathologist’s results, highlighting that the Shroud’s well-defined stains and halos contradict the washing theory.

Dr. Zugibe is not the only one questioning the shroud’s origins. Brazilian 3D digital designer Cicero Moraes has suggested that the image on the cloth likely comes from a sculpture rather than a human body. Moraes explained to Live Science: “The image on the Shroud of Turin is more consistent with a low-relief matrix. Such a matrix could have been made of wood, stone or metal and pigmented (or even heated) only in the areas of contact, producing the observed pattern.”

“There is a remote possibility that it is an imprint of a three-dimensional human body, but it is plausible to consider that artists or sculptors with sufficient knowledge could have created such a piece, either through painting or low relief,” Moraes added.

Additionally, carbon dating analysis suggests the shroud was created between A.D. 1260 and 1390, casting doubt on its legitimacy as a relic. As a result, the true origin of the Shroud remains a matter for ongoing research.