An unexpected series of discoveries is transforming our understanding of ancient Latin American societies, thanks to a fortuitous chance encounter.

In what promises to be an extraordinary tale of travel and discovery, a small team of archaeologists has been able to name an ancient civilization’s city following its discovery.

Luke Auld-Thomas, a Ph.D. candidate in Archaeology at Tulane University, made this significant find while working with a team in Mexico’s southeastern state of Campeche.

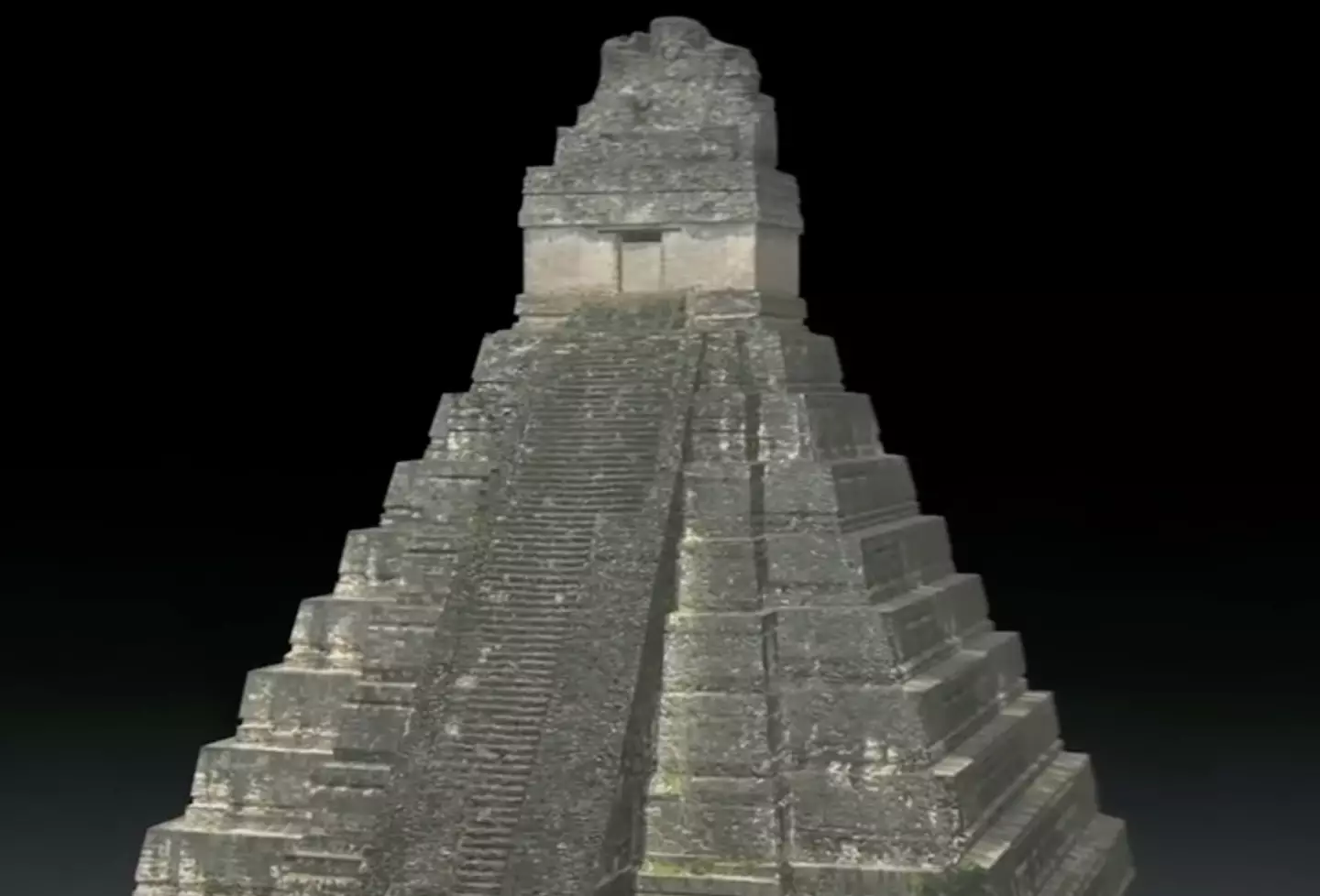

During their exploration, they uncovered pyramids, sports fields, causeways linking different districts, and amphitheaters in the ancient Maya city, which they decided to call Valeriana.

The city was named after a nearby lagoon by Auld-Thomas and his colleagues.

In total, the team identified three sites within an area the size of Edinburgh, Scotland’s capital. They stumbled across these sites ‘by accident’ while one member was browsing data online.

Auld-Thomas explained: “I was on something like page 16 of Google search and found a laser survey done by a Mexican organization for environmental monitoring.”

The technology they found themselves using was Lidar, a remote sensing method that emits thousands of laser pulses from an aircraft to map objects by measuring the time it takes for the signals to return.

When Auld-Thomas analyzed the data, he noticed what had been previously overlooked. They had discovered a vast city, believed to have housed 30-50,000 people at its height, which is estimated to have been between 750 and 850 AD, as reported by the BBC.

In a conversation with the BBC, Auld-Thomas discussed what the city might have been like, based on their findings and prior knowledge.

He described it, saying: “It would have been a very colorful, very lush, and very striking environment to move through.

“Things like palaces and temple pyramids, all of those would have been covered in lime plaster and then painted red, pink, and yellow and black.

“There would have been clusters of buildings where people mostly spent their time making ceramics or mostly spent their time shaping stone tools.

“In this part of the world, there is also some evidence of marketplaces.”

The city spanned approximately 16.6 square kilometers and featured two major centers with large buildings about 2 kilometers (1.2 miles) apart, connected by dense housing and causeways.

The archaeologists noted that the city was ‘hiding in plain sight,’ just a 15-minute hike from a major road near Xpujil, an area where predominantly Maya people reside today.