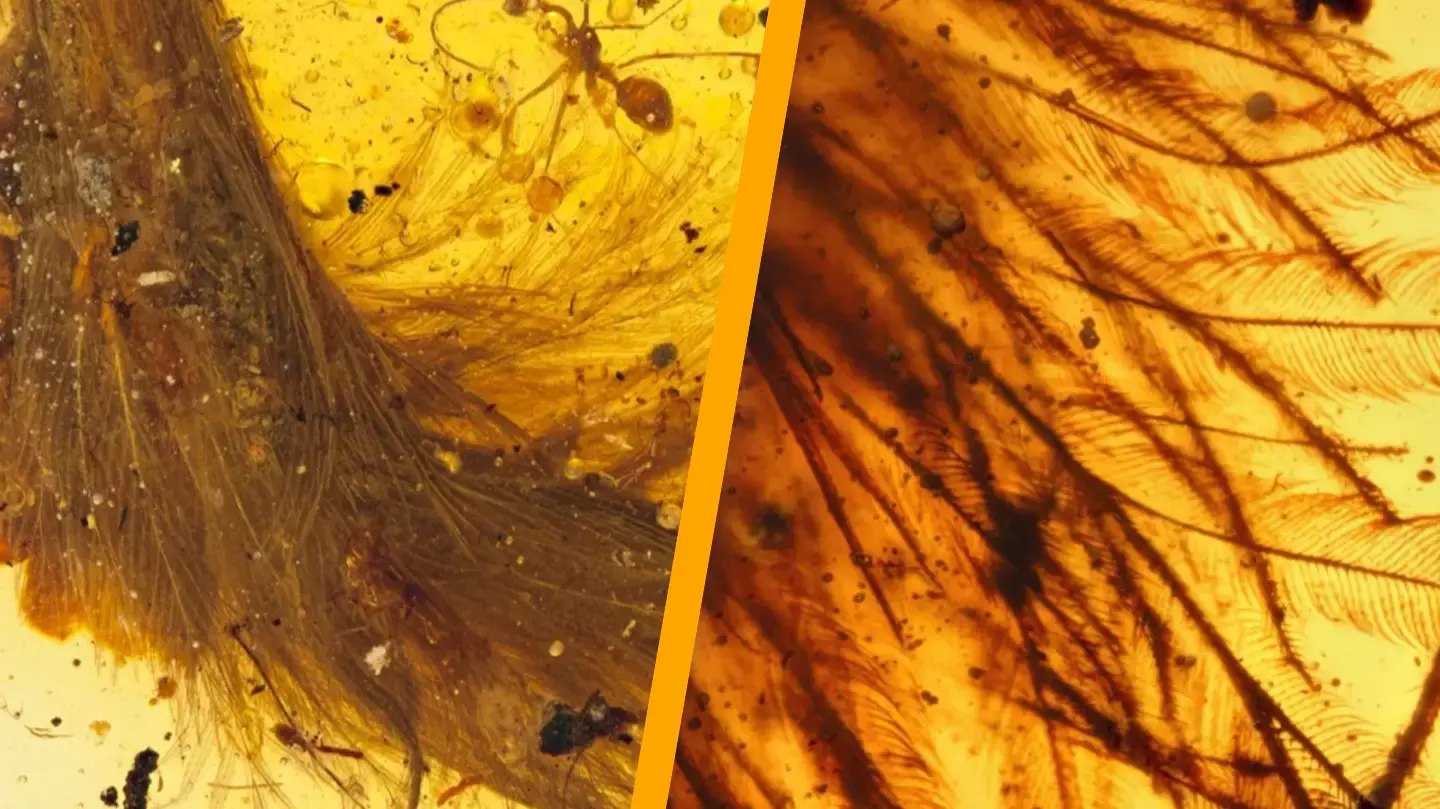

A remarkably well-preserved dinosaur tail has been found, providing fascinating insights into the appearance of these ancient creatures.

In 2016, a group of scientists uncovered a specimen estimated to be over 99 million years old.

This piece of amber contained a dinosaur tail, offering significant information about the evolution of these prehistoric animals.

The journal Current Biology notes that this piece of amber, discovered in Kachin State, Myanmar, has a unique feature visible to the naked eye—a tail with “a dense covering of feathers.”

Additional soft tissues such as muscle, ligaments, and skin are also preserved within the amber.

A previous study conducted by the same team highlights that Burmese amber deposits from this region and time are among the “most prolific and well-studied sources of exceptionally preserved” specimens from that era, but this discovery stands out.

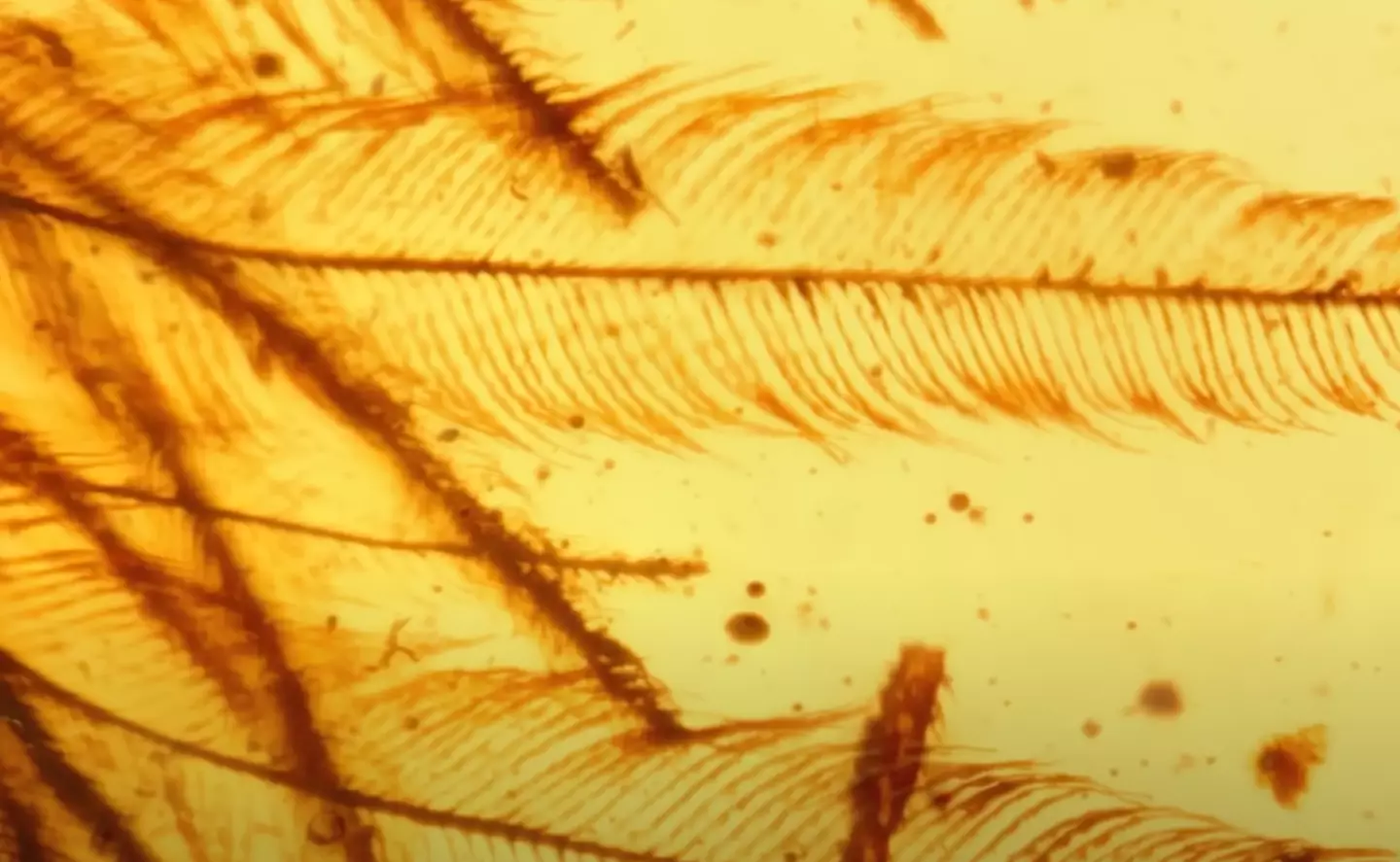

The article elaborates: “[The] plumage structure directly informs the evolutionary developmental pathway of feathers.”

“This specimen provides an opportunity to document pristine feathers in direct association with a putative juvenile coelurosaur, preserving fine morphological details, including the spatial arrangement of follicles and feathers on the body, and micrometer-scale features of the plumage.”

The tail adds to earlier discoveries that have unveiled feathers in preserved dinosaur remains.

Researchers had previously discovered wings preserved in amber that also bore feathers.

An article in Nature Communications disclosed that the Burmese amber was obtained from an amber market in northeastern Myanmar, Southeast Asia, and originates from the mid-Cretaceous period, which lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago.

The study noted: “The extremely small size and osteological development of the wings, combined with their digit proportions, strongly suggests that the remains represent precocial hatchlings of enantiornithine birds.”

“These specimens demonstrate that the plumage types associated with modern birds were present within single individuals of Enantiornithes by the Cenomanian (99 million years ago), providing insights into plumage arrangement and microstructure alongside immature skeletal remains.”

“This finding brings new detail to our understanding of infrequently preserved juveniles, including the first concrete examples of follicles, feather tracts and apteria in Cretaceous avialans.”

Chinese paleontologist Lida Xing, leader of the study, has provided further details about this ‘once in a lifetime find’.

Xing shared with CNN: “I realized that the content was a vertebrate, probably theropod, rather than any plant.”

“I was not sure that (the trader) really understood how important this specimen was, but he did not raise the price.”

Ryan McKellar, co-author of the paper and paleontologist at the Royal Saskatchewan Museum in Canada, commented: “It’s a once in a lifetime find. The finest details are visible and in three dimensions.”

“The more we see these feathered dinosaurs and how widespread the feathers are, things like a scaly velociraptor seem less and less likely and they’ve become a lot more bird like in the overall view.”

“They’re not quite the Godzilla-style scaly monsters we once thought.”