A deadly flesh-eating bacteria whose infections have spiked by 400% in the last four years is stumping medical experts in Australia.

Scientists have yet to discover what causes the disease, and where it comes from in the environment.

The global distribution of Buruli ulcer is pictured here in 2015. Infections are concentrated in central and west Africa, but Australia is one of the few places where the number is rising. In 2016, new infections jumped by 72% in Victoria. Read more: https://t.co/MVFcA50z1u pic.twitter.com/QynFTDz15y

— University of Melbourne (@unimelb) April 15, 2018

The rapid spread of the infection in regional areas of Victoria, Australia—275 newly-reported cases last year and 30 this year—has been identified as an epidemic.

The risk of infection in Victoria appears to increase during warmer months.

The Medical Journal of Australia have called for an urgent scientific response.

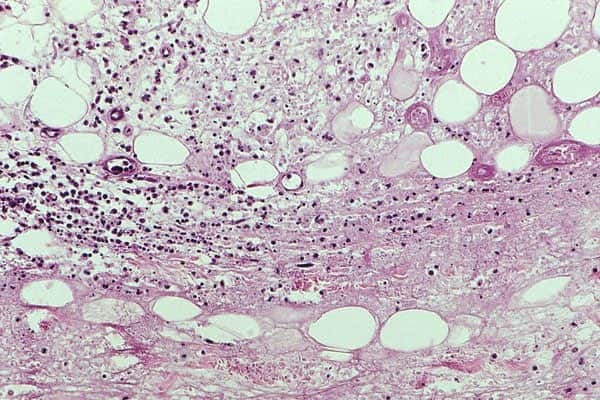

The Buruli ulcer is a chronic infection that erodes the skin and surrounding tissue. This debilitating disease is caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium ulcerans.

The World Health Organization (WHO) states that the germ is related to the family of organisms that cause tuberculosis and leprosy.

While the infection is uncommon in the US, there are approximately 2,000 cases of Buruli ulcer each year, often from West or Central Africa. Cases have been recorded in more than 33 countries to date.

According to Dr. Daniel Eiras, assistant professor of infectious diseases and immunology at NYU Langone Health, “The difference here is that it’s not well explained why we’re seeing an increase of cases in Australia whereas in essentially the rest of the world, we’re seeing a decrease in cases.”

Humans are apparently not the only species to have acquired the disease. Some mammals such as possums, dogs, cats, and koalas have reportedly shown symptoms as well.

*Fair warning to those who are squeamish—you might want to look away for the next few pictures.

During its initial stages, the infection manifests as a small, painless bump on the skin. Lesions frequently occur on the arms and legs, although doctors aren’t clear as to why.

Since there is no pain or itch, and due to the slow progression of the disease, people tend to leave it be, mistakenly thinking it would heal on its own.

Eventually, the bump turns into an ulcer or an open sore.

If left unreated, Dr. Eiras said it “will start to become larger, then it will invade the lower tissue and fatty layer under the skin and it may involve the muscle, tendons, and bone.”

One of the main symptoms of the disease is that it affects the immune system, which means the skin cannot heal.

“The bacteria do not really ‘eat flesh,’ they produce a toxin that dissolves the skin and tissue around it, but this could take weeks to months whereas an infection like staph can progress in a matter of days,” Dr. Eiras said.

Patients who suffer from this disease may also experience permanent disfiguration or disability. In severe cases, it may even lead to death.

Infectious diseases expert Professor Daniel O’Brien authored the report, which was published in the Medical Journal of Australia. He believes understanding risk factors is key to defining the source and transmission route of the disease.

“The time to act is now, and we advocate for local, regional and national governments to urgently commit to funding the research needed to stop Buruli ulcer,” O’Brien said.

Australia's localised flesh-eating bug outbreak, the Buruli ulcer, needs urgent research, and has exposed a major gap in scientific knowledge https://t.co/MVFcA50z1u #UnimelbPursuit @UniMelbMDHS @TheRMH pic.twitter.com/jGeXfUOl9q

— University of Melbourne (@UniMelb) April 15, 2018

“We are facing a rapidly worsening epidemic of a severe disease without knowing how to prevent it,” he added. “We therefore need an urgent response based on robust scientific knowledge acquired by a thorough and exhaustive examination of the environment, local fauna, human behaviour and characteristics, and the interactions between them.”

A spokesman from the Department of Health and Human Services said it was monitoring the disease and studying possum feces in the hope of isolating the bacterium.

The spokesman also said that almost $800,000 had been spent on research in Victoria over the past decade. For cases that are treated in the early stages, a combination of antibiotics such as rifampicin and clarithromycin are known to have cure rates close to 100%.