In a groundbreaking experiment, a team of researchers from Japan has successfully developed an “artificial womb” designed to incubate baby shark embryos. This marvel of science was realized by the dedicated scientists at the Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium in Motobu. Impressively, they managed to sustain the embryos of slendertail lantern sharks in the artificial environment for 355 days, nearly an entire year, shattering the previous record of 160 days.

The significance of this achievement extends beyond the duration of incubation. Baby sharks, much like premature newborns, find the saline conditions of seawater too harsh immediately following birth. This is particularly problematic for viviparous sharks, which give birth to live young rather than laying eggs.

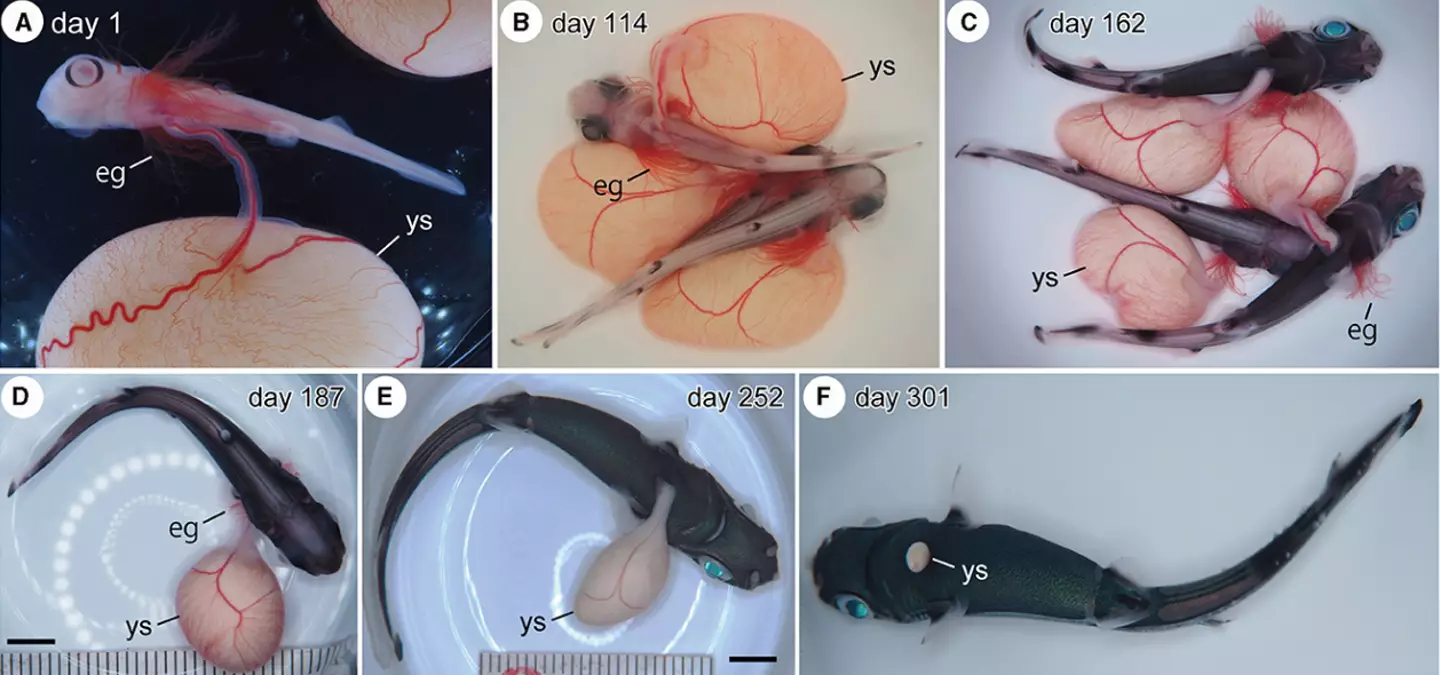

Through meticulous experimentation and adjustments, the scientists succeeded in nurturing a few mid-term embryos from a mere three centimeters to 15 centimeters, the typical length at birth. To mimic the natural conditions of a mother shark’s womb, the team crafted an artificial uterine fluid akin to shark blood plasma. They progressively adjusted the chemical composition of this fluid along with the level of exposure to seawater in their synthetic womb. Ultimately, their efforts met with success.

Despite these breakthroughs, not all outcomes were ideal. Out of 33 embryos, only three grew to a size deemed appropriate. “A total of three embryos reached birth size. Two were delivered on April 10th, 2023 (embryonic incubation period of 347 days), and the remaining were delivered on April 18th, 2023 (embryonic incubation period of 355 days),” noted the study.

Upon their ‘birth’, these sharks were immediately fed a diet of minced mackerel and shrimp and displayed behaviors typical of naturally born sharks. They are now healthy adults residing at the Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium, where, according to Haiku Magazine, they are indistinguishable from their naturally born tankmates in appearance and behavior.

Taketeru Tomita, the lead author of the study and a researcher at the Okinawa Churashima Foundation, expressed his aspirations to expand this technology. “In our aquarium, as in the outside world for conservation, we cannot select the species we receive,” he explained. “The reproductive systems of sharks have great diversity, and I think our system can only apply to about half of viviparous sharks. We would like to develop more universal systems.”

This innovative venture not only paves the way for new methods in marine biology and conservation but also offers a glimpse into the potential future of species preservation and scientific study.