Get ready to have your mind blown—a recent study suggests a 1,000-year-old buried warrior could have been non-binary!

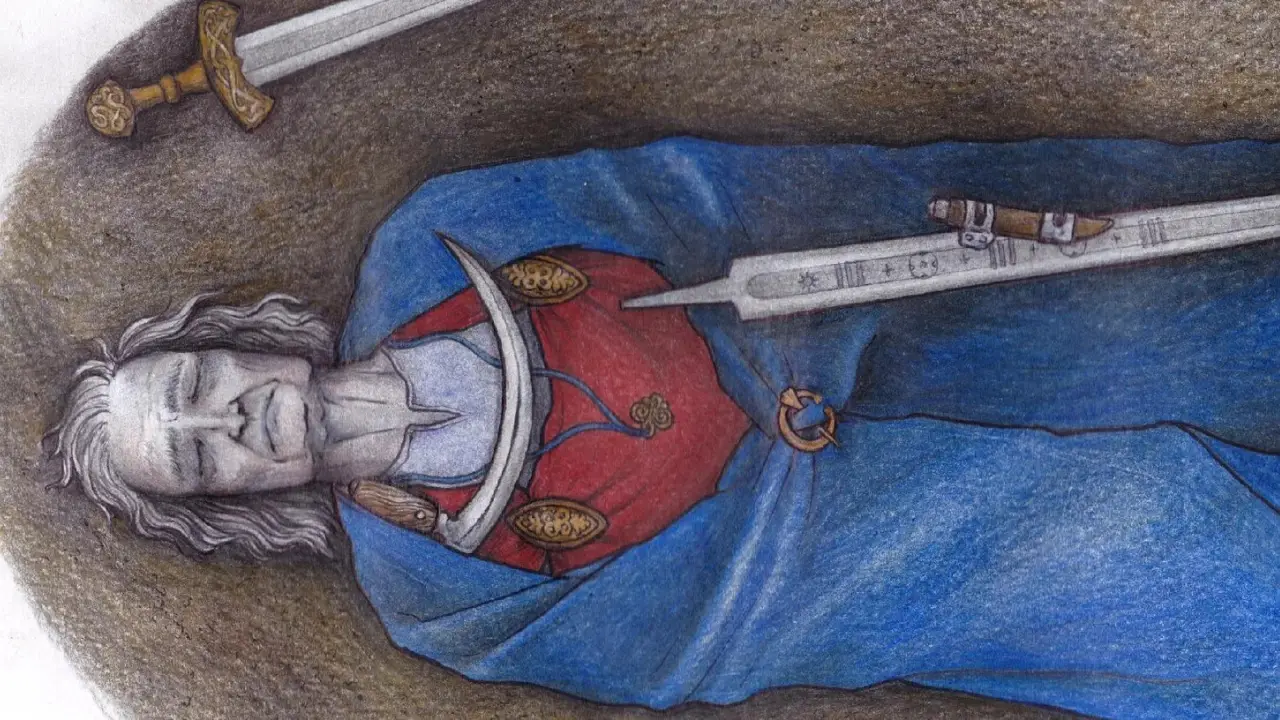

Back in 1968, archeologists in Finland stumbled upon a grave that was initially believed to house a woman, based on the era’s burial customs. The grave contained a feminine dress and jewelry, typical of a woman’s final resting place from that period.

But here’s where it gets intriguing: the grave also held two swords, an element that puzzled scientists. This led to the hypothesis that the grave might have belonged to two different individuals.

Fast forward to today, and there’s a groundbreaking twist in the narrative…

A DNA analysis featured in the European Journal of Archeology points to the remains possibly belonging to a high-status non-binary individual, according to the latest peer-reviewed study.

The LGBT Foundation defines non-binary as individuals who feel that their gender identity doesn’t fit neatly into the traditional categories of man or woman.

“This burial shows a unique and pronounced mix of feminine and masculine symbols, which might suggest the individual defied the typical gender norms of their time,” Ulla Moilanen, the study’s lead author, explained to CNN via email.

Let’s delve deeper into this ‘elaborate burial’…

The grave also contained rabbit hair, bird feathers, and brooches—elements typically associated with female burials of the time. However, the presence of a seemingly unused sword atop the body added an additional layer of mystery, described by researchers as ‘less violent and genderless’ symbolism.

The clincher came when scientists analyzed the only remaining part of the femur in the grave, revealing evidence of an XXY karyotype, often associated with Klinefelter syndrome.

According to the Cleveland Clinic, Klinefelter syndrome is a genetic condition where a person assigned male at birth has an additional X chromosome. This can lead to various physical traits, as noted by Mayo Clinic, such as reduced muscle mass and enlarged breast tissue, often without the individual ever realizing they have this condition.

Given the limited sample size, researchers had to partially rely on modeling for their analysis, yet the implications are significant.

Moilanen suggests that the individual might not have been strictly recognized as male or female by their community during the early middle ages, adding, “The lavish array of objects found with the remains indicates a high level of acceptance, respect, and value.”

This revelation is shaking up the previously conceived notion of an ‘ultramasculine environment’ in early medieval Scandinavia, with archeologists and historians calling the findings ‘exciting’, as reported by The Guardian.